Michael Hastings

Neurons and biological timing: molecular neurobiology of the circadian clock

Circadian rhythms are daily cycles of physiology and behaviour that anticipate solar day and night, allowing organisms to adapt accordingly. The rhythms persist when organisms are isolated from the external world because they are driven by internal biological clocks. They occur across all levels of life, from prokaryotes to higher plants and animals. In humans, the cycle of sleep and wakefulness is the most obvious circadian rhythm, reflecting a profound alternation of brain states.

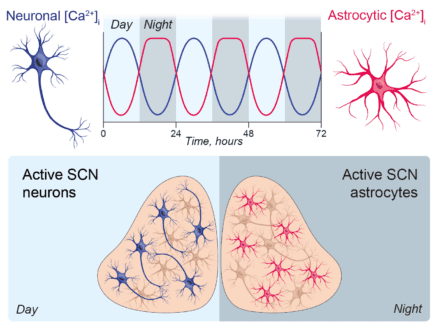

The principal circadian pacemaker is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, where individual neurons and astrocytes operate as self-sustained daily timers. The intracellular clock mechanism is also present in major organ systems, including the heart, kidney and liver. The SCN maintains synchrony among these subordinate clocks through its control over behaviour and neuroendocrine pathways. Disruption of our circadian programme through shift work, old age and neurological disease is a significant and growing cause of chronic illness.

We use real‑time in vivo fluorescence and bioluminescence imaging, omics expression analyses, synthetic biological approaches and molecular genetic manipulations in mice to understand how the ‘clock’ genes and their protein products assemble into an approximately 24-hour timekeeper, and how SCN neurons and astrocytes interact to generate these powerful timing cues. We also employ comparative approaches to understand how conserved clock genes operate in invertebrate body clocks, both daily and tidally. Through these approaches we aim to provide a molecular genetic explanation for one of the most conserved and ancient behaviours: biological time‑keeping.