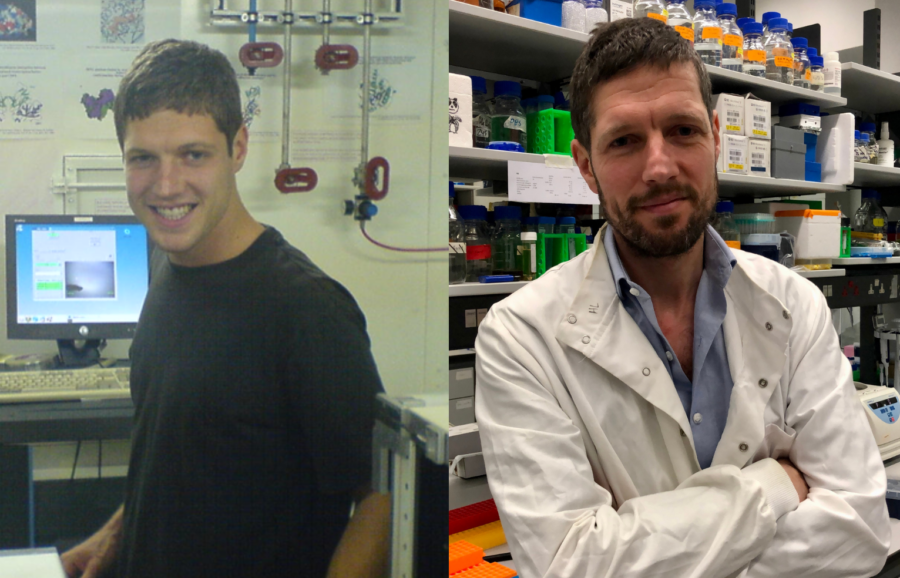

Looking Back: Harry H. Low

Harry Low was a PhD student and postdoctoral researcher in the Structural Studies Division with Jan Löwe, from 2002-2008. He is now Professor of Structural Biology and Head of Section for Structural and Synthetic Biology, Department of Infectious Disease at Imperial College London.

The summer after graduating in Biological Sciences from Oxford University in 2001, I visited Cambridge to sound out labs for a PhD. At the time I was amazed by X-ray crystallography, which enables the molecules of life to be visualised at near-atomic resolutions, including the first protein structures pioneered at the LMB. I knew I wanted to do structural biology but was unsure of the field. My first stop was a Cambridge University neurobiology lab to meet with an eminent professor – it did not go well. I was dismissed with ‘go do a master’s and decide what you want to work on!’

My next stop was the LMB to meet with Daniela Stock who’d recently managed the extraordinary feat of crystalising the F0/F1 ATP synthase complex, and Jan Löwe who’d just discovered the bacterial cytoskeleton with Linda Amos and would ultimately become my PhD supervisor. After my last meeting I was anxious, and the gallery of intimidating LMB Nobel laureates in the foyer only added to this. However, the atmosphere of both meetings was completely different, just an engaging discussion on the exciting science they were doing, non-judgmental and friendly. That was my first glimpse of LMB culture – understated, but brilliant and inspiring.

In Jan’s group, my PhD project was to show that a classical human protein called dynamin also existed and possibly had its origins in bacteria. Given its importance in the human cell as a machine for enabling nerve signalling renewal, many labs had been racing to determine its structure for over a decade. Jan’s group and the wider LMB with its remarkable concentration of outstanding scientists and resources was such an exciting, if not daunting, environment for taking on this ambitious project.

In my first week as a fledgling PhD student, I remember two occasions going up to the canteen in the elevator. The first when cheering quietly to myself as I stood beside Nobel laureate Aaron Klug, and the second having Richard Henderson, then Director of the LMB and future Nobel laureate, explaining how to correctly pronounce my supervisors name after I mispronounced it. Löwe and Low are not pronounced the same!

Back then, in the old LMB building, piles of fascinating equipment lined the sides of all the long thin corridors with no space spared and the hum of machinery accompanied you everywhere you walked. For building protein structures, I spent months sitting in a blacked-out cupboard with space for just my chair and computer screen. Not that it was expected, but I used to routinely return to the lab after dinner to do ‘the night shift’ as we called it, often joined by Thomas Leonard now a group leader at the MPL, Vienna. I loved that the LMB never slept, its doors always open, and no matter how late I was there you’d never be alone. Even in the early hours I’d pass another in the corridor, and we’d stop and chat about our experiments.

For me, the LMB was a hot pot of science that offered an outstanding training to a young researcher. It was an environment of great expectation where one was inevitably tested – certainly I remember how presenting to the whole institute during the annual Lab Talks symposium felt like a singularity of pressure, but I emerged a better scientist for it.

Last year I had the honour of returning to the LMB, now in the new building, to give a talk. Many of my old friends and colleagues who’d supported me as a student were still there, despite it being 17 years later. In this way, the LMB has a unique family quality. When I left in 2008, the late Kiyoshi Nagai, former Head of Structural Studies, told me to always work on important problems. It’s advice I’m still trying to heed in my lab today.