Realisation of the full potential of electron microscopy for the determination of biological structures at high resolution depends critically on technical advances in many different components. Important factors are the microscope electron optics, the detectors, sample preparation and computer programmes, as well as a host of smaller components.

One such component is the microscope sample holder, also known as a stage.

The development of sample holders was particularly important when moving from electron microscopy to electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM). Cryo-EM of amorphous (non-crystalline), ice-embedded specimens is a method that allows the visualisation of biological molecules in a near-native state, requiring the preservation of the specimen at a temperature below -180°C (100 Kelvin) during microscopy.

Another advantage of keeping the specimen cold was the increased electron dose, which can be used to record micrographs of organic and biological material at low temperatures. With the specimens at low temperature, the micrographs contain more information about the structures.

Initially, most commercial or laboratory prototype holders were limited in resolution to between 5 and 10 Å: a holder that could work at 3 Å resolution and would fit into a normal side-entry goniometer in a microscope was required.

“In principle, the construction of such a cryo-holder should not be difficult. In practice, however, all of our experiences with holders of this type have been fraught with resolution losses of several kinds.”

Henderson R, Raeburn C, Vigers G

Ultramicroscopy 25: 45-53 (1991)

The resolution losses were caused by vibrations and thermal expansion and contraction of the stage. The vibrations arose from both the sensitivity of the holders to ambient, airborne vibrations (sound waves) or from vibrations from the pumps providing cooling water to the microscope, as well as from internal vibrations within the cold holder due to boiling of the liquid nitrogen coolant or turbulence in the gas boiling off from the surface of the liquid. There was also a problem of slow drifting of the image, caused by a part of the holder or the microscope cooling so slowly that it never reached equilibrium, or steadily warming after that point was reached. Also, parts could move during specimen translation, making a new contact with small temperature differences between the contacting parts. These drifts could take several minutes to die out and could occur after each specimen translation.

Identifying and eliminating the design flaws in holders was crucial for improving images and determining the structures of molecules; without these developments, cryo-EM would not have achieved its level of success. Since the 1980s, the LMB has been actively involved in the continued development of improved holders and stages. We aim to make cryo-EM better, faster and cheaper for the entire biology community.

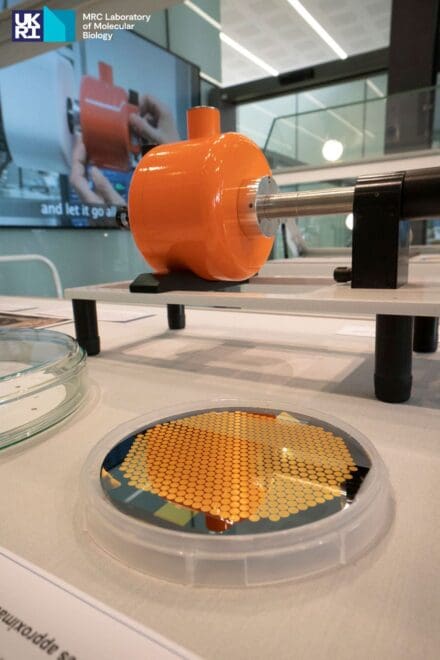

The display

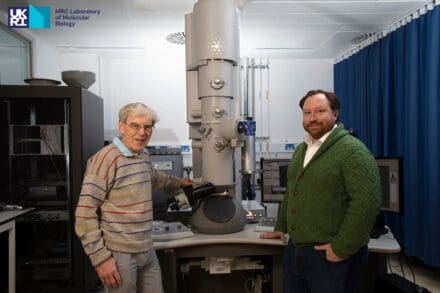

The exhibition featured the first holders used at the LMB in the 1960s, the holders developed within the LMB in the 1980s, the later commercialised holders built following the LMB’s example and the current commercial holders used frequently within the Lab today.

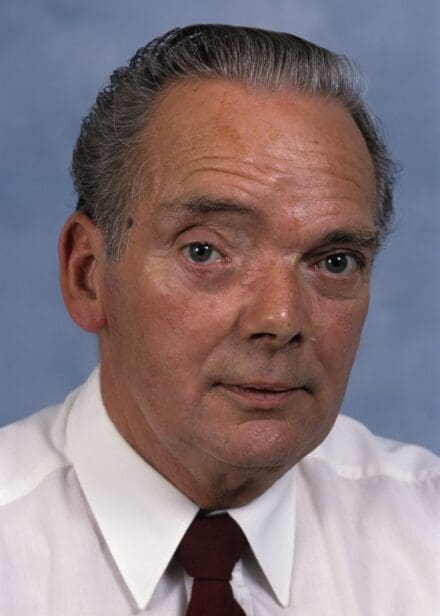

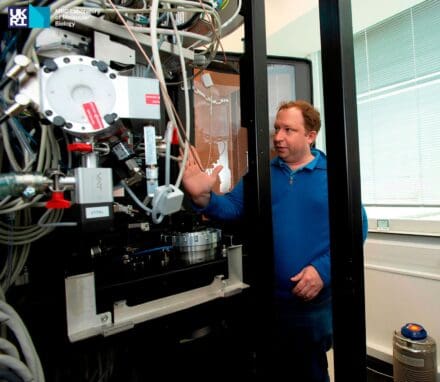

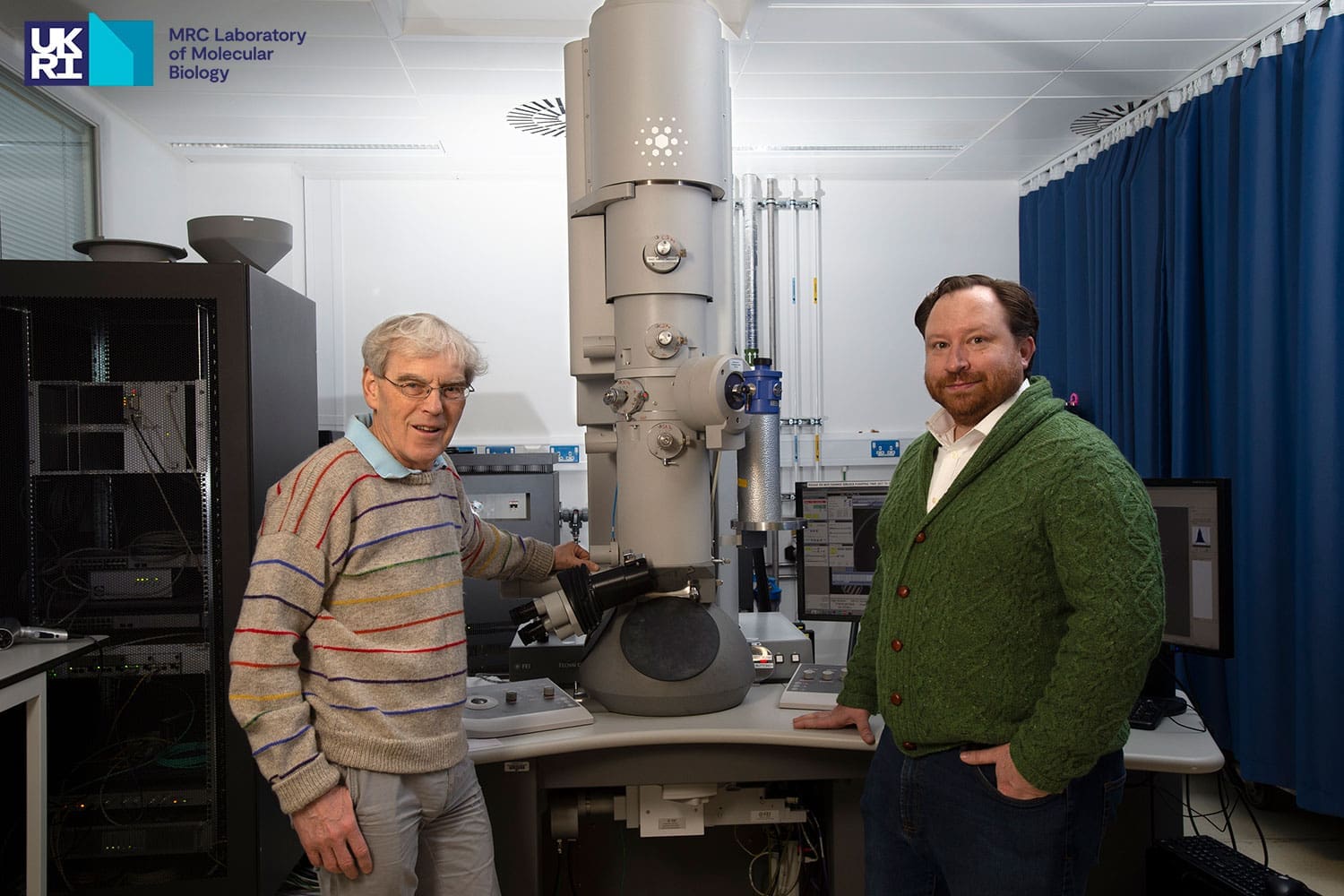

Visitors to the exhibition could also learn about the scientists behind the microscopes, and see how Nigel Unwin and Jacques Dubochet used the 1960s holders, how Richard Henderson improved the methodology of single particle cryo-EM (for which he was jointly awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) and see the holders used by Chris Russo and his group, who are working to improve the quality and functionality of electron microscopes.

Timeline of the development of cryo-EM holders

| 1962 | Commercially available Styrofoam holder for electron microscopy. Nigel Unwin (LMB) used this stage in a Philips 301 microscope, but once it reached -100 °C, it rapidly got completely covered in ice. |

| 1980‑1984 | Jacques Dubochet from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory used the 1962 holder with one of the first of the new Phillips 400 microscope series, which had a much-improved vacuum, for his pioneering work in developing the plunge-freezing method that marked the beginning of cryo‑EM. |

| 1981 | The LMB purchased a Phillips 400 microscope and quickly identified a need to improve the 1962 holder, particularly when used with nitrogen gas cooling, to eliminate vibrations. |

| 1983 | The LMB started developing its own holders. |

| 1985 | Nigel Unwin, while working at Stanford University, helped to develop a liquid-nitrogen cold-stage with Peter Swann at Gatan Inc. |

| 1991 | First LMB-developed holder: a prototype side-entry cold holder for cryo-EM was constructed to be used with no loss of image resolution or contrast at 3.4 Å resolution compared to the normal room-temperature holder. The design was commercialised by Oxford Instruments and became the Gatan CT3500. |

| 1986‑2015 | In the mid-1980s, Hexland, acquired by Oxford Instruments in 1988 and subsequently by Gatan Inc, developed improved holders. |

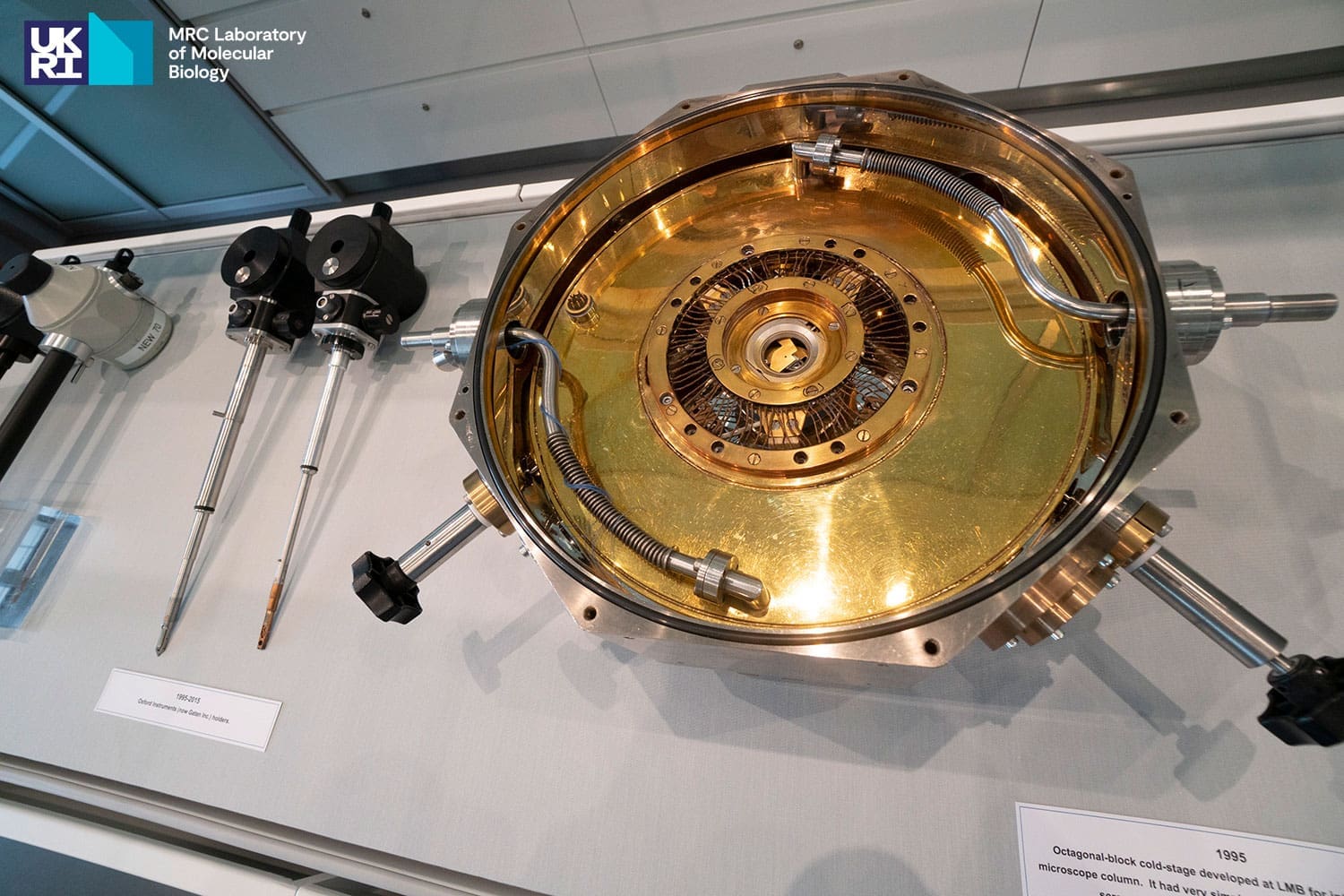

| 1995 | Octagonal-block cold-stage developed at the LMB for integration with the microscope column. It had very simple manual controls using a micrometre screw and a 5:1 reduction lever to move the sample grid. |

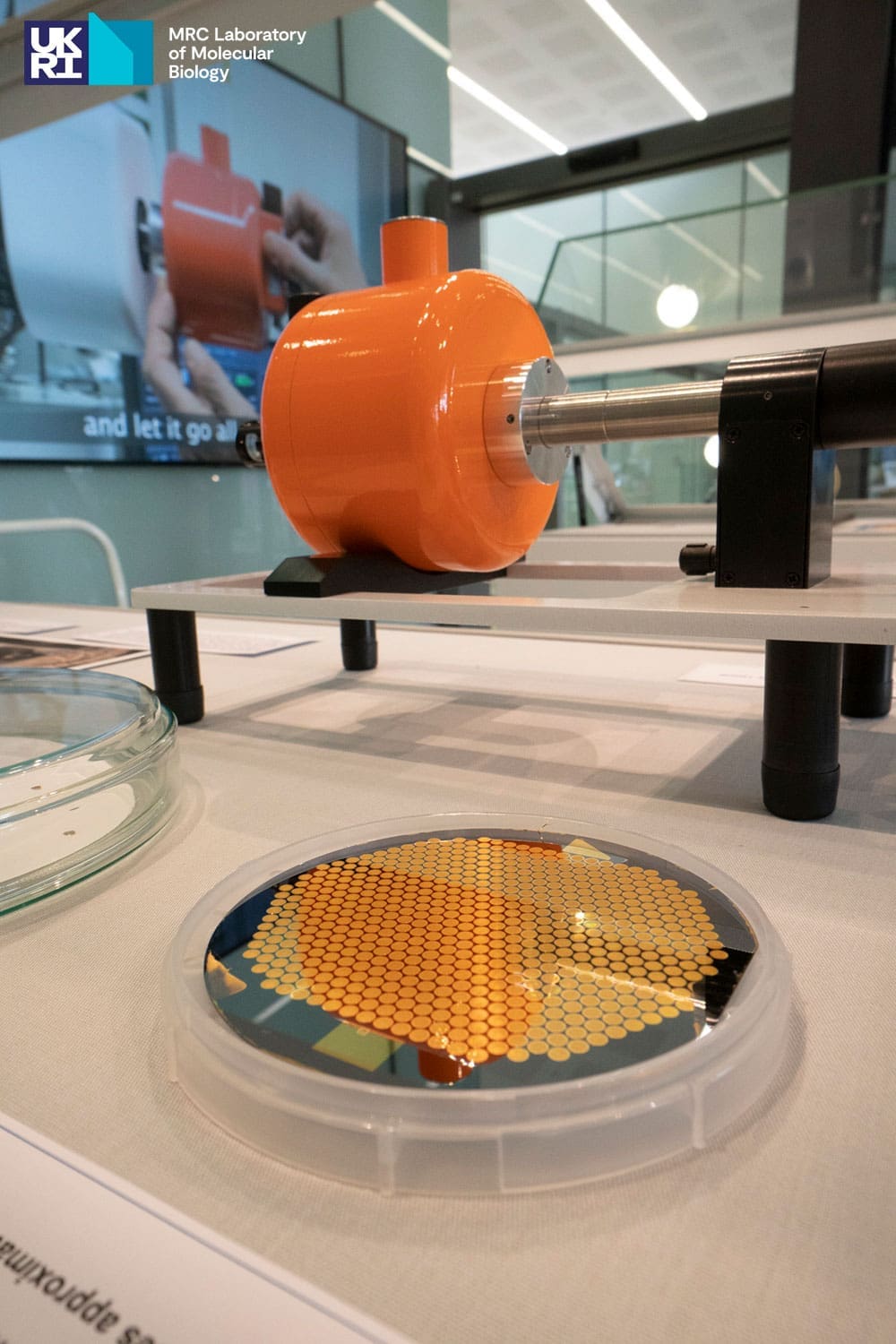

| 2020 | Current commercial holders developed for use with the JEOL 1400HR columns from Gatan Inc Simple Origin and Fischione. |

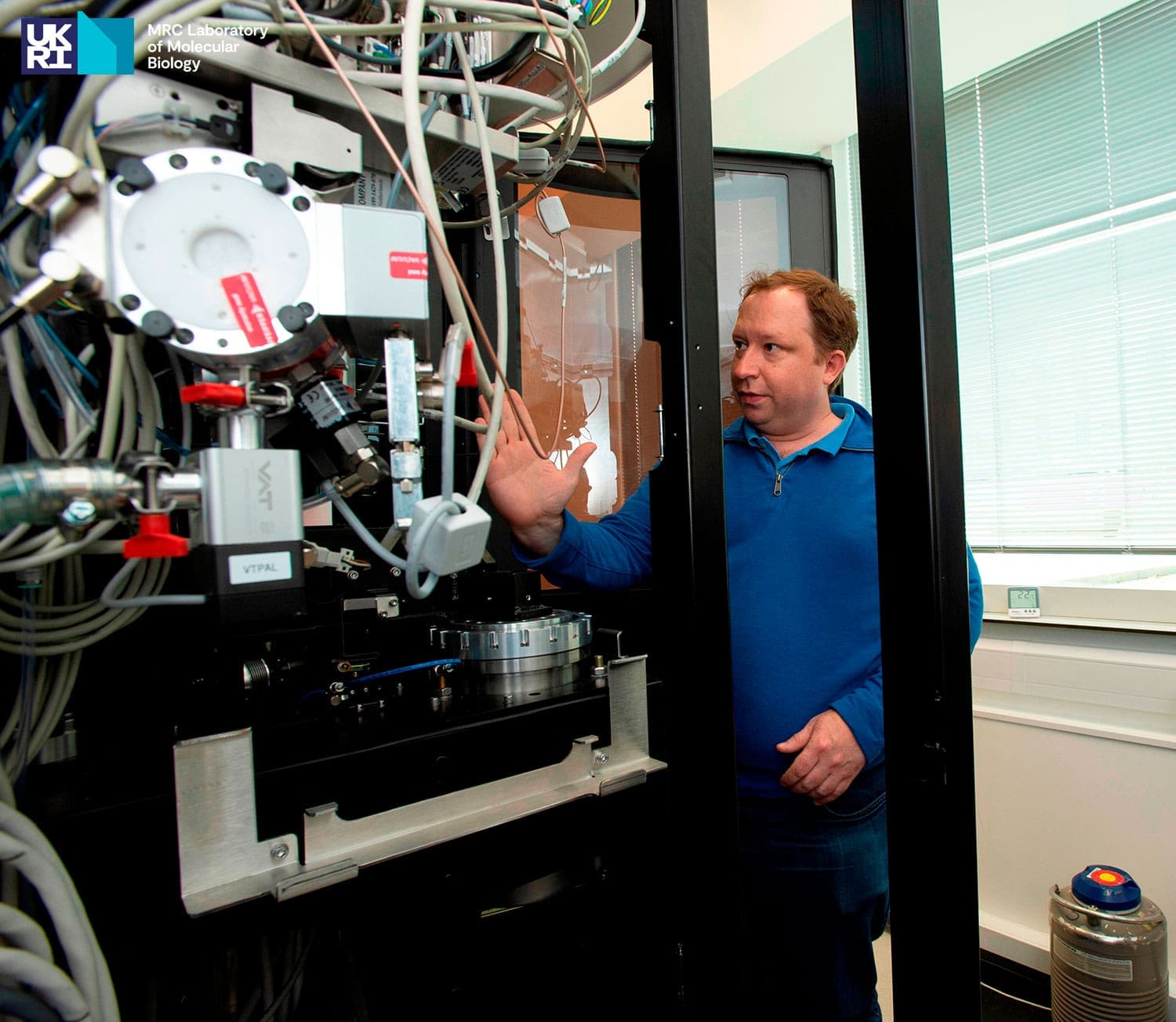

| 2021 – present | Chris Russo (LMB) is leading the project to develop a new cryostage/cryotransfer for the JEOL UK 1400 platform, with Bob Morrison acting as chief designer for the project. |