Rob Kay

How cells drink and move: macropinocytosis and chemotaxis

I studied biochemistry at UCL, where, during my PhD with Irving Johnston, I developed a classical ‘smash and fractionate’ method for isolating nuclear membranes. I was then lucky enough to join a small offshoot of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now Cancer Research UK) in Mill Hill, led by John Cairns. There I became fascinated by development and the idea that embryos are shaped by gradients of morphogens. Since no morphogens were then known, I decided to try to find one. I used the simplest organism I could – the social amoeba, Dictyostelium.

When starved, these delightful creatures form tiny, stalked fruiting bodies from thousands of amoebae. Fruiting bodies help disperse the spores, which hatch into amoebae when they encounter bacterial food again. After much effort, a morphogen was identified that induces stalk cell differentiation – DIF, a chlorinated alkylphenone. This achievement was my passport to the LMB.

Over the following decades, much was learned about animal development. The morphogens discovered in fruit flies are indeed conserved in mammals, but alas, not those discovered in Dictyostelium. So, I changed direction to work on more universal problems while keeping hold of Dictyostelium, in which I was by then an expert.

That direction led into genomics and the Dictyostelium genome project. Genetics through genomics then allowed identification of the mating locus specifying the three Dictyostelium sexes and NF1, a human cancer gene that allows amoebae to live on liquid medium.

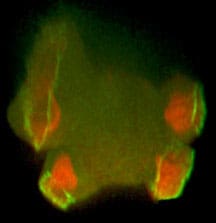

Amoebae, like human neutrophils, are very active. They move along chemical gradients (chemotaxis), eat bacteria (phagocytosis) and can drink their medium prodigiously (macropinocytosis). These conserved processes were central to my later career. They are driven by the actin cytoskeleton and the signals shaping it into pseudopods or cups.

Recently, I have focussed on macropinocytosis. Amoebae and cancer cells use it for feeding and it is also a route into cells for viruses and vaccines. With collaborators, I discovered key macropinocytic genes and how cups are shaped around domains of PIP3 in the plasma membrane, leading (post retirement) to a model for how cups form and close. I continue to extend this work.